It’s all things phosphorus these days. My survey about the phosphorus targets you use in practice is still live (and available here). Plus, I just released my new Hyperphosphatemia Assessment Cheat Sheet (which you can download here). So today, I am reviewing this article which focuses on managing hyperphosphatemia for people receiving dialysis.

Why are low phosphorus diets recommended?

For people living with kidney disease, evidence has demonstrated that those with hyperphosphatemia have a higher mortality risk. This has lead to recommendations to reduce dietary phosphorus intake.

However, there is still a lack of data demonstrating that lowering serum phosphate levels actually improves clinical outcomes, such as death, for our patients. As such the newest nutrition guidelines in CKD no longer specific a target dietary phosphorus intake. Citing a lack of evidence for any specific target.

What is a low phosphorus diet?

When I first started working in renal, we set a low-phosphorus diet at a limit of 800–1000 mg of dietary phosphorus per day. However, as the authors newer guidelines have dropped this target due to a lack of efficacy that this actually worked.

In practice, clinicians often treat hyperphosphatemia by giving people a list of high-phosphorus foods to reduce or avoid. However, there is concern that this may result in:

- Patient’s making less healthy food choices if they restrict healthy high phosphorus foods such as whole grains, nuts, seeds and legumes

- Inadequate protein intake (for those on dialysis) because most high protein foods also contain phosphorus

- Negative impacts to quality of life by making it harder to eat with friends and family.

Where does phosphorus come from?

Processed foods, which may contain phosphorus additives, are a major concern for phosphorus intake. The challenge with these foods is that labeling laws prevent patients and clinicians from determining how much phosphorus has been added. This means that foods that were previously low in phosphorus may now be substantial sources. Additionally, the phosphorus from these sources is likely more bioavailable than phosphorus found naturally in foods.

The authors of this paper highlight that medications can be a significant source of phosphorus and report previous findings of up to 200 mg of phosphate per tablet.

What are phosphate binders?

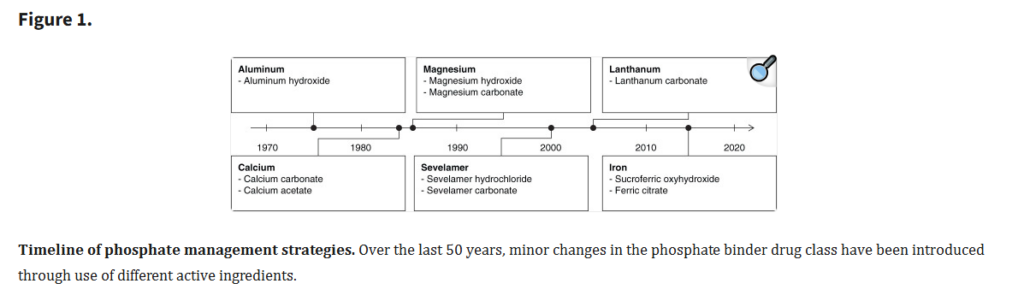

In the renal world, clinicians often prescribe phosphate binders, commonly called binders, to help patients reduce phosphorus absorption from foods. They were first introduced in the 1970s as aluminum salts.

Figure 1 of the article shows that since the 1970s, clinicians have phased out aluminum salts and introduced new binders.

How much phosphorus will binders bind?

The type of binder determines how much dietary phosphorus each tablet binds, but most estimates indicate that even at the maximum dose, binders can only bind about 300 mg of phosphate per day.

| Binder | Frequently Prescribed Doses | Binding capacity (mg P/g binder) | Daily Binding Capacity |

| Sevelamer Carbonate | 1-2 800mg tablets per meal (3-6 per day) | 26.3mg/g | 63-126mg |

| Calcium Acetate | 2 tablets per meal (6 tablets per day) | 45mg/g | 180mg |

How much phosphorus do people eat?

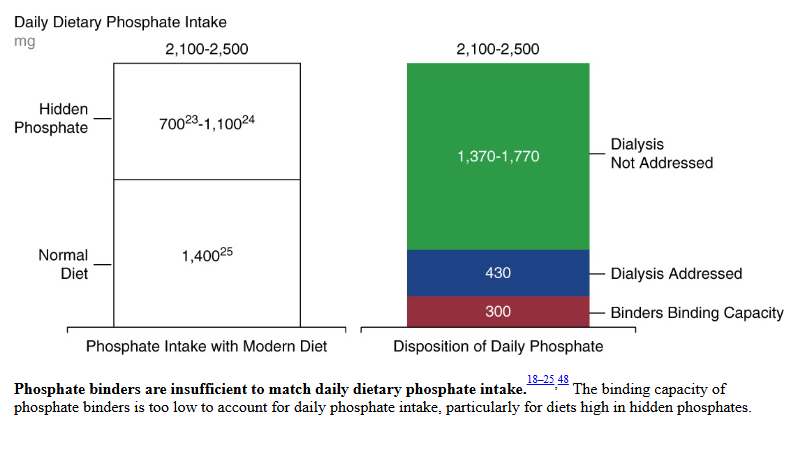

Ok, so the next logical question is if binders can remove a max of 300mg per day, however much phosphorus are people consuming. The authors report that a normal dietary phosphorus intake sits around 1400mg per day. They add on an additional 700-1100mg from phosphorus additives, for a grand total of 2100-2500mg per day.

How much phosphorus is removed by dialysis?

The authors report that an average of 430mg of phosphorus is removed by dialysis. Though this didn’t discuss what type of dialysis (HD vs PD) and if HD is that per session, meaning there would be no phosphorus removal on days off, or is this averaged over the week. So clearly a question for another blog post.

But you can see from their figure 2 – that with binders and dialysis, there remains an additional 1370-1770mg of phosphorus intake not addressed.

How do phosphate binders impact patients?

Evidence suggests that phosphate binders negatively impact patient’s quality of life in multiple ways, including:

- Contributing substantially to pill burden, with a median count of 9 per day, though sometimes by 15-20 binders prescribed per day.

- Burdensome timing – binders need to be taken with meals or snacks which makes remembering them very challenging

- GI upset – including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and constipation.

The authors go on to summarize that data from January 2021 reported that 69% of people receiving dialysis in the USA had phosphorus levels above recommended targets. Which suggests, not surprisingly, that current binder options aren’t working.

If current therapies aren’t working, what else can be done?

The authors go on to discuss Tenapanor, which is a novel class of phosphorus binder that inhibits absorption of phosphate at the paracellular level in the intestine.

Tenapanor was the big topic when I attended to the 2024 National Kidney Foundation Spring Clinical Meeting in Long Beach California. So, if you want to read more about that, check out some of my other blog posts here.

Take Aways

Getting serum phosphate levels to target using standard therapies is incredibly difficult, if not down right impossible for some people. Between the current high phosphorus food source, low quality medication options and inadequate phosphorus removal from dialysis, people and clinicians working to get levels to target have an uphill battle.

So as a clinician what can I do? For me, I think this means, be realistic. Be realistic with my patients on what we can expect from standard therapy. And be realistic when talking with my colleagues in ensuring they know what we can expect from standard therapy.

Are you working with patients with hyperphosphatemia? Have you downloaded my hyperphosphatemia assessment cheat sheet? If not, get it here.

One thought on “Why managing hyperphosphatemia feels like pushing a stone uphill”