Speakers: Christine Corbett, Joanna Hudson, Kathleen Hill Gallant, Kristal Higgins

This is a summary of a presentation I attended at the National Kidney Foundation Spring Clinical Meeting in May of 2024.

What hormones help manage serum phosphorus levels

Three hormones help manage serum phosphorus levels – including FGF23, PTH and 1,25D. As 1,25 declines, FGF23 and PTH increase with a goal of increasing urinary phosphorus losses. Eventually, as these mechanisms become overwhelmed, serum phosphorus levels will rise.

The consequences of these changes lead to:

- CVD

- Bone Changes

- Kidney Disease progression

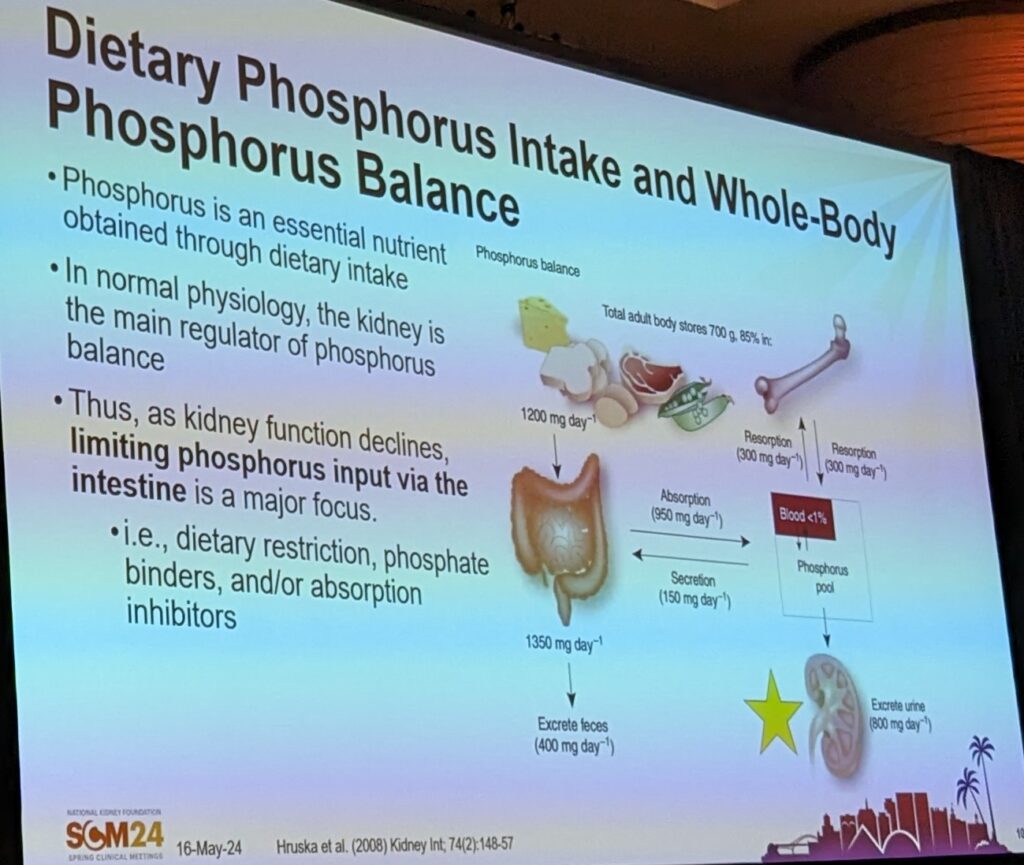

How is phosphorus balance maintained?

The majority of the phosphorus in our body is maintained in bone, though we measure serum phosphorus levels. The main phosphorus inputs are mainly from diet, though in lesser quantities from medications. In a normal kidney, any excess phosphorus is excreted.

As kidney function declines, we can look at how the intestines can help maintain balance through absorption inhibitors.

How is phosphorus absorbed in the gut?

There are two main intestinal absorption pathways for phosphorus:

- Transcellular pathways – active at low phosphorus intake, mediated by transporters and can get saturated, increased by 1,25 D

- Paracellular pathway – is a linear pathway, related to intestinal lumen concentration and dietary intake loads. The new drug tenapanor inhibits phosphorus absorption at the paracellular pathway.

What dietary approaches are used to control phosphorus?

- Traditional – limit foods high in PO4

- Focus on PO4 to protein ratios

- Source/bioavailability approach

What is a traditional low PO4 diet?

Most adults consume ~1400mg PO4 daily. This is about twice as much as the RDA at 700mg for adults. In the current guidelines, there is no specified level for dietary PO4 intake, the goal is individualization. However, the 2010 Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics guidelines recommend aiming for 800-1000mg or 10-12mg per gram protein per day.

Traditional diet recommends avoiding whole grains, high fibre foods, most dairy products, nuts, seeds, beans and legumes. And foods with phosphate additives. Instead, it is recommended to consume animal protein, refined grains, rice or almond milk, and low phosphorus dairy products (e.g. butter, cream cheese, heavy cream).

What are the concerns with traditional low phosphorus diet approaches?

Traditional low phosphorus diet restricts foods that otherwise considered healthy and evidence suggests that higher consumption of these foods may be associated with improved health outcomes for adults living with kidney disease, including:

- Gut microbiome

- CVD health

- Acid-base balance

- High Mg consumption (which may help with other improved health outcomes)

What are the benefits of considering phosphorus to protein ratios?

One challenge is that protein intake and phosphorus intake are tightly correlated. Furthermore, evidence suggests that hyperphosphatemia is associated with increased mortality, while inadequate protein intake is also associated with increased mortality risk. Studies have linked that decreases in protein intake and phosphorus intake are associated with poorer mortality.

Therefore, restricting foods that are lower in phosphorus while being higher in protein can help lower phosphorus intake while ensuring adequate protein intake. This is why consideration of the phosphorus to protein ratio has been proposed as one approach to help manage phosphorus intake.

Why consider the food source of the phosphorus?

When you consider the bioavailability the phosphorus load changes. Load will be total amount of phosphorus * anticipated bioavailability.

Evidence suggests that when patients are taught to avoid phosphorus additives that they have better serum phosphorus levels than those who were not taught to read labels.

Additionally, when more plant protein is used in place of meat protein, serum phosphorus levels were improved.

How does cooking impact bio-accessibility in plant proteins?

Cooking methods can reduce phytate activity and make phosphorus more bio-accessible. However, cooking methods can also reduce the total phosphorus content, which may make the net phosphorus availability lower.

What is the link between phosphorus intake and serum levels?

There is a weak correlation link between phosphorus intake. If you see abnormal phosphorus and dietary sources have been considered, consider that it is possible that abnormal phosphorus levels can be related abnormal bone turnover.

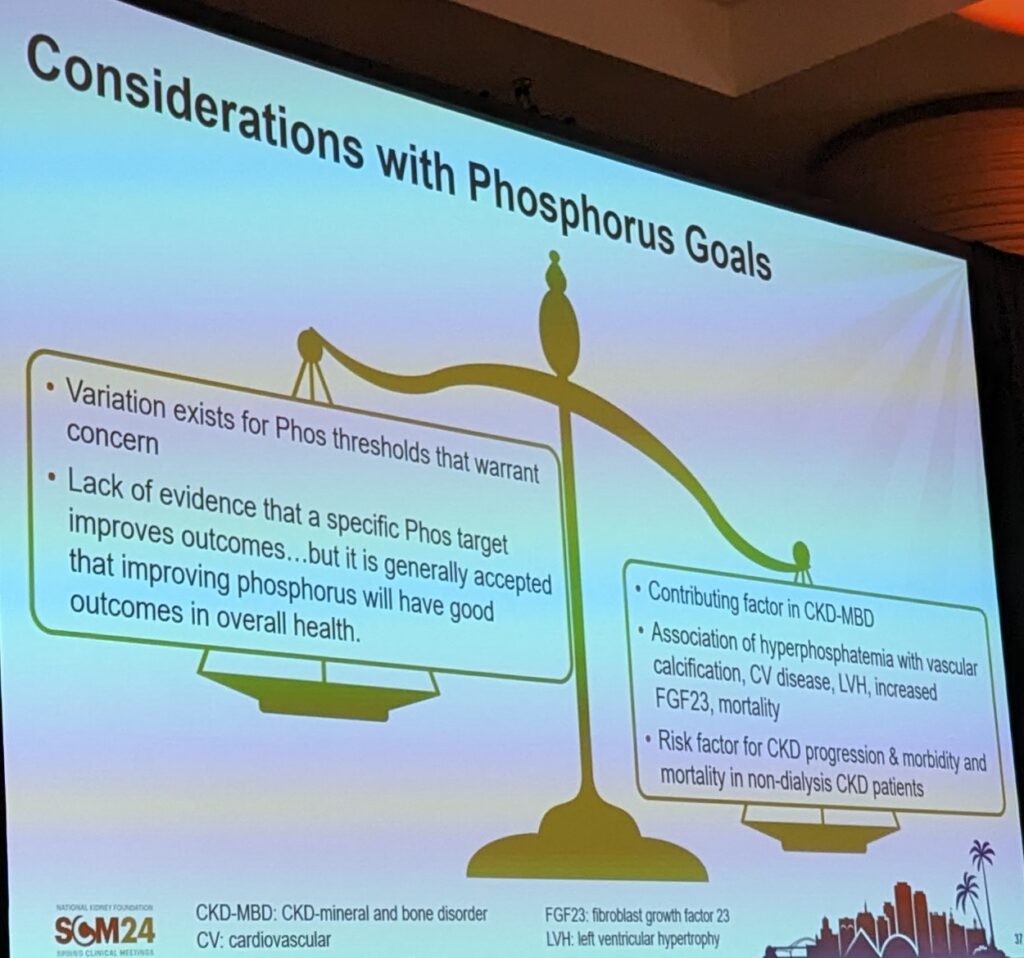

Why control phosphorus?

Elevated phosphorus is associated with mortality. But, there is lack of evidence for specific phosphorus targets to improve outcomes.

What phosphorus levels should we target?

Newest guidelines suggest trying to achieve normal serum phosphorus levels while avoiding hypercalcemia. But about 40% of people on HD have hyperphosphatemia.

How can we manage phosphorus levels?

- Control phosphorus – diet, binders and dialysis

- Avoid hypo and hypercalcemia – limit calcium from binders and diet

- Control PTH – vitamin D, calcimetics

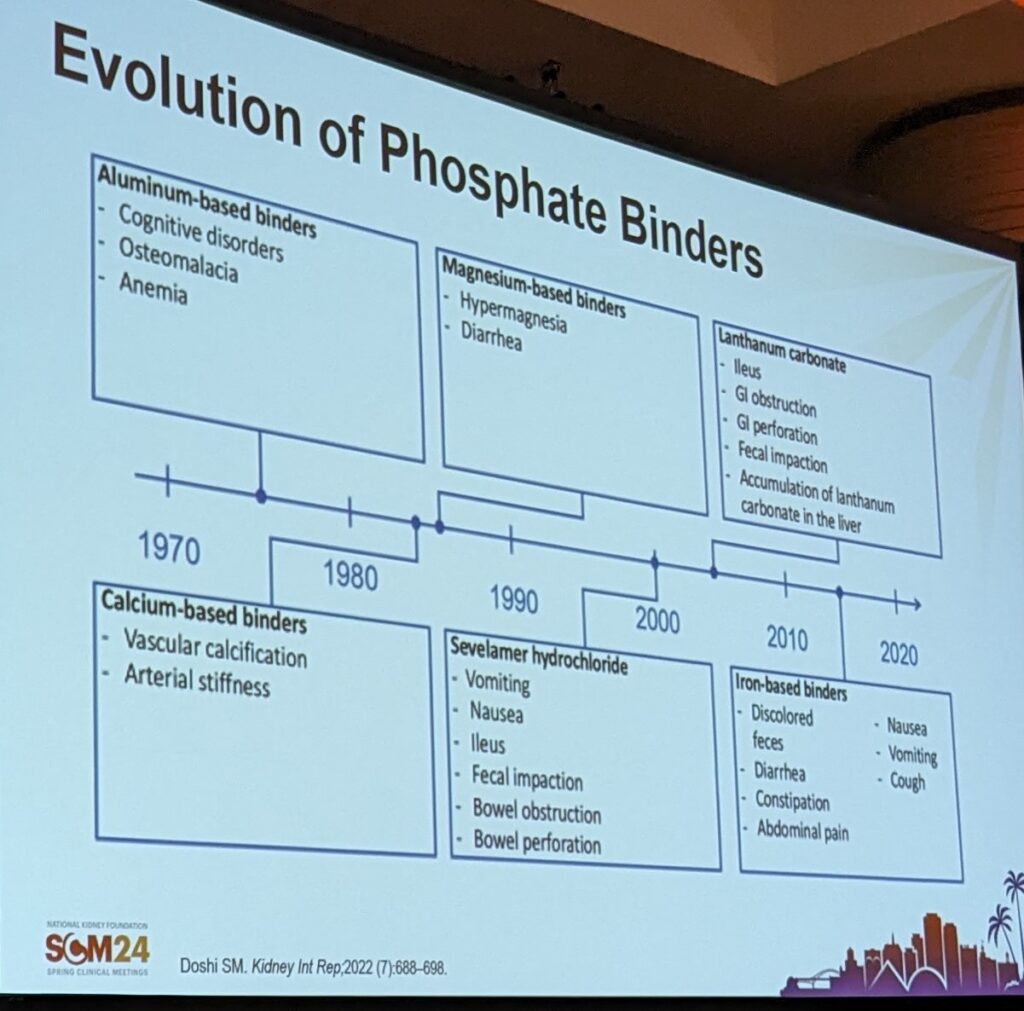

What are our phosphorus binder options?

Phosphorus binders have evolved over time, however each of them have their own pros and cons. The concern with calcium based binders is atherosclerotic, arteriosclerosis and calciphylaxis. Newer binders continue to cause some GI concerns.

Of note for lanthanum – requires chewing. Swallowed whole can cause complications.

Newest binders are iron based – sucroferric oxyhydroxide and ferric citrate.

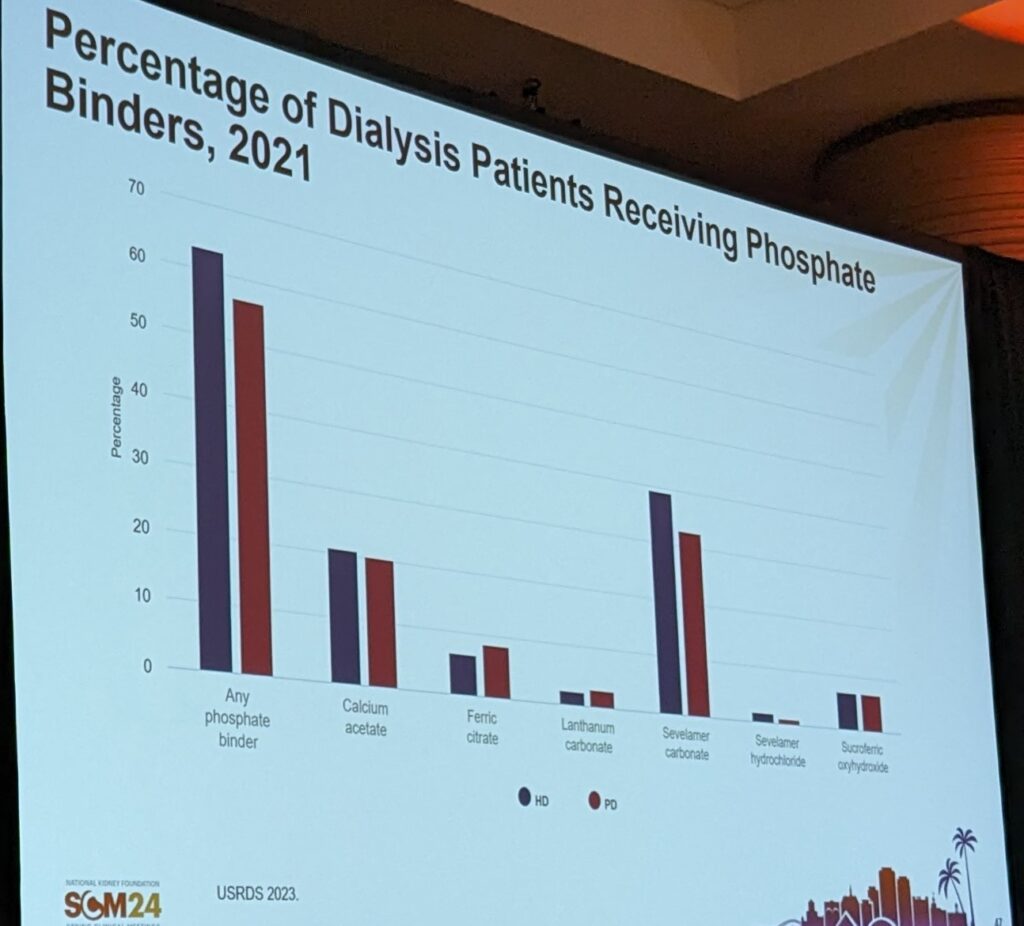

What types of binders are people taking (in the USA)?

Of note calcium carbonate wasn’t captured in this data.

What are the patient perspectives on PO4 binders?

- Pill burden (could be as many as 10 phosphorus binders per day)

- Adverse effects

- Take with meals

- Drug interactions

- Cost/access

Why do we switch PO4 binders?

- PO4 not controlled

- Hypercalcemia – stopping calcium

- Pill burden (which may prompt a switch to Velphoro)

- Intolerance to binders

- Patient preference

This presentation summary continues in the next blog post, which you can find here. The topic of the next post is: Novel Mechanisms for Phosphorus Lowering – Introducing Tenapanor.

One thought on “Phosphorus Management: Walking the Tightrope”